More than 1.06 million people were living with diagnosed HIV in the United States at the end of 2019, and almost 37,000 were newly diagnosed during the prior year, according to the latest Medical Monitoring Project (MMP) report from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The report shows that people diagnosed with HIV face many challenges that contribute to racial/ethnic and other disparities in the U.S. epidemic.

The MMP is a cross-sectional, nationally representative survey that assesses behavioral and clinical characteristics of adults with diagnosed HIV in the United States. Started in 2009, the MMP initially collected data from adults receiving HIV care, but it was expanded in 2015 to include all adults with diagnosed HIV regardless of care status. These data “are critical for achieving the goals of the National HIV/AIDS Strategy and the Ending the HIV Epidemic in the U.S. initiative, which seek to reduce new HIV infections in the United States by 90% by 2030,” the report authors wrote in their commentary.

For the latest report, researchers reached out to 9,700 people with diagnosed HIV in 16 states and Puerto Rico, of whom 3,710 agreed to participate. Data were collected from June 2020 through May 2021.

Source: Medical Monitoring Project, 2020 CycleCenters for Disease Control and Prevention

Three quarters of the participants were cisgender men, 23% were cisgender women and 2% were transgender. An estimated 45% identified as gay or lesbian, 43% as heterosexual or straight, 9% as bisexual and 3% as another sexual orientation.

The proportion of older people living with HIV has been increasing, and 55% of people included in this survey were over age 50. People ages 40 to 49 accounted for 19% of respondents, those ages 30 to 39 for 18% and those ages 18 to 29 for 8%.

This report confirms that HIV disproportionately affects Black and Latino Americans, underlining the importance of targeted care and outreach for these groups. In this analysis, 42% of people with diagnosed HIV were Black, 29% were white, 24% were Latino and 6% were another race or ethnicity. When accounting for their share of the total population, Black Americans are 3.4 times more likely, and Latinos are 1.3 times more likely, to be diagnosed with HIV.

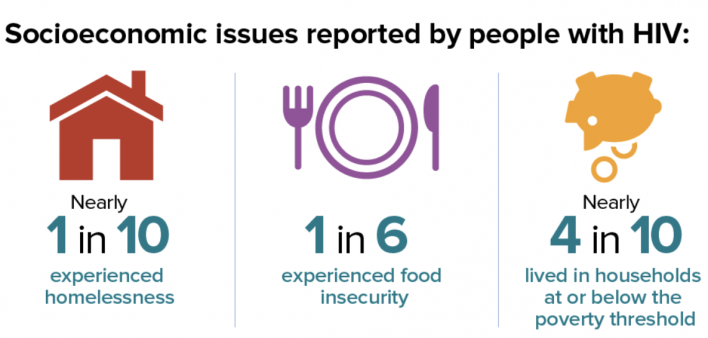

People with diagnosed HIV were more likely than the population at large to face socioeconomic challenges that can make it more difficult to maintain good health, including poverty, unemployment and homelessness.

About 40% of survey respondents had a high school education or less, and about 17% were not born in a U.S. state or territory. More than a third (36%) had a household income below the poverty line, three times the national poverty rate. About 40% were unemployed, over six times the national rate. Approximately 16% said they experienced food insecurity, or going without food due to lack of money. It should be noted that these figures reflect the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic, so might not be representative of other years.

In this analysis, 8% experienced homelessness—almost four times the national rate—and the likelihood of unstable housing was even higher: approximately 12% had moved in with other people because of financial problems, 8% had moved two or more times and 2% had been evicted during the past year. Unstable housing can be a risk factor for acquiring HIV and having a higher viral load. Nearly 4% had been incarcerated for more than 24 hours. About a quarter (26%) had ever experienced intimate partner violence, including 4% during the past year.

Fortunately, despite high levels of poverty and unemployment, 98% reported having some form of health insurance or coverage for care or medications, including 47% with coverage through the Ryan White HIV/AIDS program, 43% with Medicaid, 28% with Medicare and 40% with private health insurance.

Overall, 72% of respondents perceived their general health as being good to excellent, although 40% had a disability. More than two-thirds (68%) had been diagnosed with HIV at least 10 years earlier, and 54% had ever been diagnosed with AIDS. Overall, they had a high mean CD4 count (659 cells), but 7% had a count below 200.

Most respondents (95%) had received some outpatient HIV care during the past year. About 72% remained in care for the entire past year and 56% did so for the past two years. Concerningly, an estimated 38% were seen in an emergency department at least once, 4% were seen five or more times and 16% were admitted to a hospital at least once. Some aspects of care fell short. Just 42% of those with an indication for Pneumocystis pneumonia prophylaxis had a prescription for it, and only around half of sexually active people were tested for sexually transmitted infections. The most frequently cited unmet needs were dental care (21%), food assistance (15%), mental health services (8%) and shelter or housing services (8%).

The vast majority of participants (95%) reported taking antiretroviral therapy during the past year, although just 79% had a prescription documented in their medical record. Those who had previously taken antiretrovirals but were not currently doing so cited problems with money or insurance (37%), lack of an active prescription (29%) or fear that the medications would sicken or harm them (20%). But among those taking antiretrovirals, 78% said they had never been troubled and 12% had rarely been troubled by side effects during the past month.

A majority of people on treatment (62%) said they had not missed a dose during the past month. Those who missed doses said they forgot to take their pills (65%), had interruptions to their routine (39%), slept through a scheduled dose (37%) or felt depressed or overwhelmed (16%).

More than half (59%) maintained viral suppression (a viral load less than 200) for the entire past year. This falls short of UNAIDS 90-90-90 goals, which call for 90% of people on treatment to have an undetectable viral load.

The report reveals racial disparities in who was prescribed and taking antiretroviral therapy. Black people were less likely to have an active antiretroviral prescription than their white and Latino peers (76%, 81% and 81%, respectively). Reported treatment adherence was somewhat lower for Black and Latino people compared with their white peers (60% versus 66%). An estimated 54% of Black people had sustained viral suppression, compared with 63% of Latino people and 62% of white people.

Source: Medical Monitoring Project, 2020 CycleCenters for Disease Control and Prevention

The survey included questions about sexual behavior and HIV prevention strategies. About 40% of men and 50% of women reported that they did not have vaginal or anal sex during the past year. An estimated 62% of sexually active gay and bisexual men had sex with sustained viral suppression, which prevents HIV transmission (undetectable equals untransmittable, or U=U). More than half (55%) used condoms, 54% had sex with another HIV-positive person and 22% had condomless sex with a partner on pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP).

Among sexually active heterosexual men with HIV, 57% used condoms, 50% relied on U=U, 24% had sex with an HIV-positive partner and 5% had sex with a partner on PrEP. Sexually active women with HIV mainly relied on U=U (58%) and condoms (51%) while 28% had sex with an HIV-positive partner and just 4% had sex with a partner on PrEP. These figures reflect the low rates of PrEP use among women and heterosexual men at risk for HIV. Just 13% of sexually active gay and bisexual men and 14% of heterosexual men and women reported having sex without any sort of prevention.

The survey also asked about substance use, mental health and stigma. Nearly a third (29%) smoked tobacco, 63% reported drinking alcohol (though only 7% did so daily), and 29% used marijuana. Less than 10% reported using methamphetamines, cocaine, club drugs or prescription tranquilizers or opioids. An estimated 3% reported injection drug use (2% meth and 1% heroin).

An estimated 14% reported depression and 18% reported anxiety. On a 10-question battery to assess stigma around HIV status, the median stigma score was 28 (on a scale of 1 to 100) for the past year—a great improvement from 2017, when the median score was 39

Click here to read the full Medical Monitoring Project report.

Comments

Comments