Throughout much of the current decade, a bleak statistic identifying just how dismally the United States health care system cares for people living with HIV has served as a constant rallying cry. Sadly, researchers have estimated that only about 30 percent of the U.S. HIV population is on antiretroviral (ARV) treatment for the virus with an undetectable, or fully suppressed, viral load.

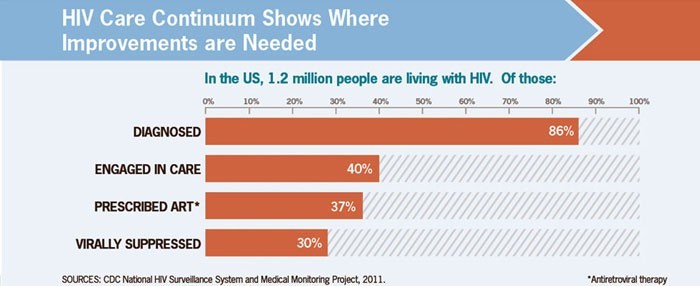

This estimate, which the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) made based on 2011 data, is the last step in what is known as the HIV care continuum, the sequential stages required to successfully treat the virus: diagnosis, linkage to medical care, linkage to and engagement in care, prescription of ARVs and viral suppression. Meanwhile, the treatment cascade, a term that is sometimes used interchangeably with the care continuum, refers to the series of descending figures that reflect the proportion of people achieving each of these key steps.

According to the 2011 estimate, out of 1.2 million HIV-positive U.S. residents, 86 percent have been diagnosed, 40 percent are in regular medical care, 37 percent have been prescribed ARVs and 30 percent have a fully suppressed virus.

AIDS.gov

AIDS.gov

The official U.S. care continuum figures are embarrassingly low compared with other Western nations, and by now even some poorer nations. The U.S. statistics highlight the missed potential in not just reducing the risk of sickness and death among people living with HIV but also preventing the virus’s spread. Research increasingly shows a strong health benefit to treating the virus as early as possible and that fully suppressing the virus likely all but eliminates the chance of transmission to others.

There is reason to believe, however, that the official U.S. treatment cascade figures were underestimates to begin with. And mounting evidence suggests that the viral suppression rate has otherwise been improving in recent years.

One recent paper in the Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes, which relied on a different and arguably more reliable methodology to estimate the U.S. treatment cascade figures, put the 2011 HIV population at just 819,200, with 86 percent diagnosed, 72 percent retained in care, 68 percent on ARVs and a more solid 55 percent virally suppressed. A separate paper, published recently in The Lancet HIV, has estimated that 833,030 people were living with HIV in 2015, with 70 percent of them on ARVs.

On another optimistic front, increasing viral suppression was likely instrumental in driving the six-year 18 percent drop in the CDC’s estimate of the annual number of HIV transmissions between 2008 and 2014. Announced in February, this decline followed two decades of frustrating stagnation in the national HIV transmission rate.

“The declines in annual HIV infections are likely due, in large part, to efforts to an increase in the number of people living with HIV who know their HIV status and are virally suppressed,” says Sonia Singh, PhD, an epidemiologist at the CDC’s Division of HIV/AIDS Prevention.

Courtesy of CDC

The CDC is currently developing a long-awaited revision to the official national treatment cascade figures, a process that involves determining the most reliable methods of arriving at the estimates.

In the meantime, various states and cities have striven to improve their own HIV surveillance efforts—including by doing a better job of parsing their local HIV population to determine who has moved away and who has actually been lost to care—and to develop local treatment cascade estimates. Along with the recent findings from academic and CDC research of different components of the U.S. care continuum, these trenchant analyses have revealed considerable nuance hidden within the cascade’s rather blunt infographic.

By exposing key racial, age group, HIV transmission category, sex and geographic disparities at the various stages of the care continuum, researchers are refining their ability to identify various obstacles, such as lack of reliable public transportation to an HIV clinic, that frustrate what ideally would be a fluid and rapid transition between contracting HIV and receiving effective, ongoing treatment for the virus.

As national figures look up, racial disparities persist.

Currently, 32 states plus Washington, DC, are part of the expanding body of jurisdictions that provide rich enough data for the CDC to conduct particularly refined analyses of components of the care continuum—helping uncover worrisome disparities as well as hopeful signs of progress. These 33 jurisdictions account for perhaps 620,000 people who were living with diagnosed HIV in 2013, or about 70 percent of the CDC’s estimate of the national population of those diagnosed with the virus.

A recent CDC report found that in these jurisdictions, 72 percent of Blacks and 79 percent of whites who received an HIV diagnosis in 2014 were promptly linked to care for the virus. Among the population living with diagnosed HIV in these jurisdictions at the end of 2013, 54 percent of Blacks and 58 percent of whites were retained in regular HIV-related medical care, and, in a troubling disparity, a respective 49 percent and 62 percent had a fully suppressed viral load.

This report further broke down the differences in treatment cascade statistics among subgroups of African-Americans with HIV. Those who injected drugs or who were younger and contracted the virus through heterosexual sex appear to have had a harder time progressing through the various steps in the care continuum and, according to the CDC, may need tailored interventions to help them along the way.

Reviewing data from the same 33 jurisdictions, the CDC also recently found that 57 percent of people living with diagnosed HIV in 2014 were virally suppressed according to their last viral load test. However, just 48 percent had an undetectable viral load throughout that year. Such durable viral suppression rates were lower among those who contracted HIV through injection drug use or heterosexual sex compared with MSM and lower among women compared with men, younger individuals compared with older individuals, and Blacks compared with Latinos and whites.

A different CDC study recently looked at about 23,000 HIV-positive members of an ongoing cohort and found that between 2009 and 2013, the proportion with an undetectable vial load at their last test rose from 72 percent to 80 percent. Meanwhile, the proportion of those with durable viral suppression throughout the previous year increased from 58 percent to 68 percent during the same time.

Further solidifying the sense that viral suppression rates are on the rise, an increasing proportion of people in care for HIV have a viral load below 1,500, according to another recent CDC analysis. Looking at a median 5.4 years of follow-up data on nearly 6,000 HIV-positive members of an ongoing cohort drawn from nine U.S. cities, researchers at the agency found that the proportion of the group’s overall time spent with a viral load above this threshold was 37 percent in 2000 and 40 percent in 2003 (at that point in time, taking structured breaks from ARVs, which were proved harmful in 2006, were still in vogue) and then fell steadily to just 10 percent in 2014.

Viral load and antiretroviral treatment (ART) data on 6,000 HIV-positive members of an ongoing cohort Courtesy of CDC

Another recent CDC study analyzed responses to the 2008, 2011 and 2014 National HIV Behavioral Surveillance (NHBS) survey of men who have sex with men (MSM) in 20 major urban areas to determine HIV care and treatment trends among the demographic. While the study sample is not nationally representative, the researchers nevertheless observed that linkage to care and treatment rates are apparently improving among MSM.

Among those diagnosed with HIV during the three years prior to each NHBS survey, those who reported being linked to care within one month of diagnosis increased from 75 percent in 2008 to 78 percent in 2014. The proportion of those living with the virus who reported being on ARVs increased from 69 percent in 2008 to 88 percent in 2014. Across the years of the study, ARV use rates were higher among whites, older individuals and those with more education, higher incomes and health insurance.

As a part of its recent analysis of 2008 to 2014 HIV transmission rates, the CDC also found that the proportion of HIV-positive MSM who did not know they had the virus dropped in all racial groups during that period, with telling disparities persisting. In 2014, an estimated 20 percent of African-American, 21 percent of Latino and 13 percent of white MSM with HIV had not been diagnosed.

City- and state-specific data

“There’s a saying in these circles that ‘all public health is local,’” says Patrick Sullivan, PhD, a professor of epidemiology at Emory University’s Rollins School of Public Health and a former HIV surveillance expert at the CDC.

Indeed, while the CDC can help states and cities with their local HIV surveillance efforts in particular, when it comes to responding to the findings about these sorts of data sets, such public health interventions are generally driven on a local level.

Addressing efforts to improve the accuracy of the national care cascade estimate and reconcile findings from different related analyses, Sullivan says, “One of the things that’s really been a puzzle is that when you have this national number and then you look at what the states and the cities are calculating as their own numbers, the state and city numbers look substantially better. But if the states and cities that make up the great proportion of the epidemic are doing better, how do you sync that across?”

Sullivan helms the new website HIVContinuum.org, which provides an impressive series of charts and interactive maps detailing finely siloed statistics about the care continuum in various U.S. cities as well as the states of Texas and Illinois. The site provides a rich visual representation of the way that improved surveillance tools and data sets regarding local HIV epidemics can help cities better tailor their responses.

Some cities have marked impressive milestones in the effort to bring the virus to heel. At the 2017 Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections (CROI) in February, the host city Seattle’s county health department announced that the rainy city’s surrounding King County was one of the first major counties in the country to hit the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS’s (UNAIDS) so-called 90-90-90 target.

In 2014, UNAIDS called upon nations to get 90 percent of their HIV populations diagnosed, 90 percent of that group on ARVs and 90 percent of that group virally suppressed by 2020. This translates to a 73 percent overall rate of viral suppression and, according to UNAIDS models, would be instrumental in sending the epidemic into retreat.

Thanks to significant local campaigns to greatly increase control of their own epidemics, New York and San Francisco are nipping at Seattle’s heels.

Out of San Francisco’s 2014 HIV population, an estimated 93 percent were diagnosed, 75 percent had received HIV care, 59 percent were retained in care and 67 percent were virally suppressed. (The estimated corresponding figures for the state of California are 91 percent, 64 percent, 49 percent and 52 percent.) These figures have almost certainly improved over the past three years thanks to the city’s full-court press against the virus.

(Note that such figures don’t directly correspond to the 90-90-90 formula, since all have the same denominator—the overall HIV population—whereas each of the points in the UNAIDS target has a different denominator.)

The San Francisco and California 2014 care continuum statisticsCourtesy of Dr. Susan Scheer, SFDPH, 2015 HIV Epidemiology Report

Susan P. Buchbinder, MD, director of Bridge HIV, an HIV prevention unit at the San Francisco Department of Public Health, attributes the city’s recent successes in controlling its own epidemic to multiple factors, including cooperation between and enthusiastic engagement on the part of nonprofits, community members, academia, the health department and health care providers, as well as a significant financial investment from city government.

“We also share with other jurisdictions the fragmentation of our medical and psychosocial care systems, which make it more challenging for providers to track patients lost to follow-up and the churn of patients through various insurance programs and health providers,” Buchbinder notes. Addressing possible future political attacks on the Affordable Care Act (ACA, or Obamacare), she continues, “That could get worse with changes to the ACA, [which] certainly may affect most heavily those jurisdictions that don’t build backup systems to ensure access to care for our most vulnerable patients.”

Susan Buchbinder of UCSF at the opening session of the 2017 Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections in SeattleCourtesy of Benjamin Ryan

Meanwhile, in 2015, an estimated 94 percent of HIV-positive New York City residents were diagnosed, 86 percent were retained in care, 82 percent were prescribed ARVs and 74 percent were virally suppressed. Translated to the 90-90-90 format, these figures amount to a 94-87-90 metric of success. So the city only needs to bring up its ARV treatment rate by three percentage points to hit the UNAIDS benchmark.

As is true across the country, a major part of the challenge New York City faces when improving its care continuum statistics is the need to address racial disparities. The 2015 viral suppression rate among those living with diagnosed HIV (as opposed to the whole HIV population) was 74 percent among Blacks, 80 percent among Latinos, and 88 percent among whites. When breaking down the numbers by age, adolescents and young adult New Yorkers are the least likely to have an undetectable viral load; viral suppression rates apparently increase steadily among progressively older age brackets.

New York City 2015 care continuum statisticsCourtesy of New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene

New York City 2015 statistics of viral suppression rates among those diagnosed with HIV, broken down by raceCourtesy of New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene

As such progressive cities lead the way in fighting HIV, cities and states in the South lag behind on numerous measures. The CDC estimates that in 2012, statewide diagnosis rates ranged from a low of 77 percent in Louisiana to a high of 93 percent in New York and Hawaii; Colorado, Connecticut and Delaware also had a greater than 90 percent diagnosis rate. Seventy percent of the states with the worst diagnosis rates were in the South.

CDC

In the 2011 and 2014 NHBS surveys, the South had the lowest ARV use rate among HIV-positive MSM compared with other regions. Researchers believe this difference is driven by widening racial disparities, given the Southern HIV population’s higher proportion of African Americans.

In Atlanta, where metrics of prevention and treatment of the virus can reveal a discouraging portrait of the local epidemic—an estimated 12 percent of young black MSM contract HIV each year—the disparity in care continuum statistics between Blacks and whites may be a by-product of transportation factors, according to Sullivan. Recent research has found that the lengthy commute time and cumbersome public transportation options between predominantly African-American neighborhoods and HIV testing sites and care providers presents a major obstacle to diagnosis and treatment of the virus among local Blacks.

Sullivan says that such neighborhood-level data "is a critical part of getting HIV prevention and care right. As we develop new ways to draw out where HIV services are needed and where services are being provided, that information literally becomes a roadmap for improving access to services."

This map of engagement in HIV care disparities among Atlantans living with the virus shows a section in the southwest, comprised of predominantly Black neighborhoods, where engagement is lower, likely because of transportation obstacles.HIV Continuum

CDC

1 Comment

1 Comment