If you’re not familiar with the work and world of fashion illustrator Antonio Lopez, then I envy you—because you have a wonderful discovery ahead. He first got my attention while I was reading back issues from POZ’s debut year, 1994. (POZ is a sister publication of Tu Salud; it focuses on the HIV community.) An article in the magazine titled “Antonio Lopez’s Illustrated Legacy” included a memorable portfolio of his colorful and energetic work.

This intriguing powerhouse of a man influenced art, fashion and music from his breakout in the 1960s until his death of AIDS-related illness at age 44 in 1987. I wanted to know more!

The opening spread of a 1994 POZ article about Antonio

For starters, there’s the fabulous 2017 documentary Antonio Lopez 1970: Sex, Fashion and Disco (watch the trailer posted atop this article) and The Antonio Archives—you’ll gag over the archive’s Instagram feed and Facebook posts (hello: vintage Jessica Lange, Pat Cleveland and Grace Jones Polaroids). But an unexpected opportunity to delve into Antonio’s work—he signed his work “Antonio” so it seems natural we’re on a first-name basis—presented itself this spring with the scheduled opening in New York City of the art exhibitions Antonio Lopez: Let Me Hear Your Body Talk at Daniel Cooney Fine Art and Studio 54: Night Magic at the Brooklyn Museum (Antonio is the subject of a third exhibit, though this one is at the Fondazione Sozzani in Milan, Italy).

For a scheduled POZ feature, I emailed New York gallery owner and director Daniel Cooney as well as Paul Caranicas, who runs The Antonio Archives. But before the article was published, the coronavirus arrived, shut down the city and killed the story.

Fast-forward to the end of June: Amid the political turmoil, Black Lives Matter protests and virtual Pride events, Gotham is ever so cautiously reopening. The Brooklyn Museum remains shuttered, but Daniel Cooney Fine Art is now open by appointment, and Antonio’s legacy feels more relevant than ever. Find out for yourself. Below is our email exchange from early March, edited and updated for length and clarity.

First off, how were you introduced to Antonio’s work? Did you know him?

Daniel Cooney: Sadly, I only know Antonio through his work and the books and film made about his life. I don’t recall my first introduction to Antonio’s work, although I have been aware of him for many years. The illustrator Richard Haines is a huge fan, and Richard brought his work into my orbit in a serious way. My friend Cory Grant Tippin, who was good friends with Antonio, introduced me to Paul Caranicas, who runs The Antonio Archives.

Paul Caranicas: I met Antonio and his collaborator Juan Ramos in 1971 while I was living in Paris and studying at the École des Beaux Arts. They had relocated from New York to Paris a few years earlier after becoming frustrated with the commercialization of the American publishing world. Juan became my partner shortly after, and I lived with them for the remainder of both of their lives.

Antonio Lopez and Juan Ramos, c. 1968Courtesy of The Antonio Archives/Harold Chapman

How would you describe Antonio’s work, and what was revolutionary about it?

DC: Antonio’s work was revolutionary in so many ways when he hit the scene in the 1960s. He truly brought the hand of the illustrator to life in a new way. As most illustrators were trying their best to duplicate what they saw, he introduced movement and energized mark making. Most importantly, he introduced his own energy and enthusiasm, which in itself was revolutionary for illustration.

PC: Antonio and Juan were both originally from Puerto Rico but raised in New York. Their worldview as gay Nuyoricans put them in a unique position and allowed them to incorporate gender and racial awareness into their work in a way that had not existed in the fashion world before. Additionally, Juan in particular was deeply inspired by art history and often drew on various themes and artists of the past and present as inspiration.

Tell us about the collection of pieces at the gallery and how they fit into the larger context of Antonio’s work and life.

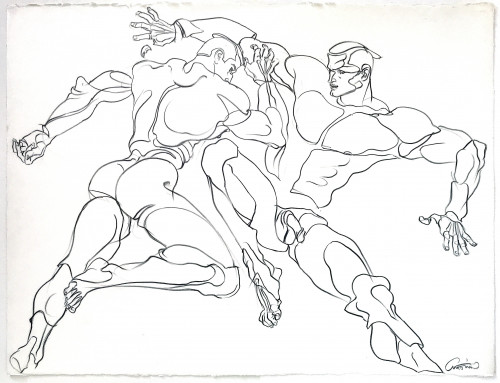

DC: We are exhibiting figure studies of dancers made in 1982 and 1985. The group from 1982 [consists of] large-scale watercolors. The 1985 works are small pencil drawings. The models for the ’85 drawings are dancers from the Louis Falco Dance Company. Falco was Antonio’s partner at the time.

Body Study, models unknown, 1982, 31“ x 23”Courtesy of Daniel Cooney Fine Art/Antonio Lopez

These particular drawings have never been exhibited until now. As Antonio is known primarily as a fashion illustrator, this work is unusual, as the focus is on the body. Antonio’s joy with drawing the human form is evident in the gestural markings and the care with which he addresses the human body. The work is highly energetic and incredibly fun.

Body Study, model unknown, (c) 1982, 31“ x 23” (This drawing is matted and 34“ x 26”)Courtesy of Daniel Cooney Fine Art/Antonio Lopez

PC: By the early 1980s, Antonio and Juan were spending more time on their personal work, which focused on the portrait. After years of working in fashion, these drawings and paintings depart from the clothed body and show Antonio’s interest in breaking down the human anatomy. The naked body had long been a source of inspiration and was previously explored both in photography and in works on paper. Having Louis Falco as his boyfriend gave him the opportunity to have an array of highly flexible and accomplished dancers to work with and pose in unique ways.

Fans of the awesome ’80s will recognize the title of the exhibition as a line from Olivia Newton John’s smash hit “Physical.” Why that title? What’s the connection between the pop hit and your show?

DC: The title was the suggestion of Paul Caranicas and [his niece] Devon Caranicas at The Antonio Archives. It’s perfect, as it just sums it all up! It reminds me of my high school years in the 1980s checking out the flimsy gym attire on hunky dudes in Olivia Newton John’s videos. It also refers to Antonio’s special blend of play, rhythm and queer desire that perfectly captures the zeitgeist of its time, while also alluding to Antonio’s signature use of live models.

The gallery show was meant to coincide with the Brooklyn Museum’s exhibit Studio 54: Night Magic, about the legendary nightclub. What can you tell us about Antonio’s presence in that show?

PC: Studio 54: Night Magic, curated by Matthew Yokobosky, is a look back at the design, social politics and history of the nightclub. Antonio and Juan played an integral role in the opening night on April 26, 1977, for which they designed the costumes and staged the iconic Alvin Ailey Dance Theater performance, choreographed by Kay Thompson. Serendipitously, as the exhibition was being curated, we came across a box of the original costume sketches and clothing swatches that were made for the performance, and we also rediscovered a series of 35mm slides, taken by Juan, of the fittings and rehearsals. These archival materials are all shown in the exhibition, as well as Antonio’s personal diary recounting the opening night and other ephemera.

Antonio was much more than a talented illustrator. What are some of his other projects, and in what ways did he influence culture?

PC: Antonio and Juan were both artists and incredible creative talents. Throughout their lifetimes, they took photographs, designed jewelry, textiles and clothing, collaborated with stores such as Bloomingdale’s and Fiorucci and, of course, produced a huge body of personal work.

Was Antonio open about his sexuality and HIV/AIDS status?

PC: Antonio was bisexual and very open about his sexuality. He was diagnosed [with HIV] in 1984 and spent the next three years undertaking experimental treatments until he ultimately passed away from complications related to AIDS in 1987. He wasn’t open about his status until the final year or so.

Why do you think his work and his story remain relevant today—and tomorrow?

DC: Antonio exuded a chic sexiness that naturally drew people to him. He was also exceptionally talented and smart. His work is relevant because it changed the story of fashion illustration and fashion itself. He was the first to embrace models of color and to challenge the status quo. Coming from a Puerto Rican immigrant home and making it big in an industry that was rigidly white is a success story on its own. And, most importantly, he had a great time doing it!

PC: Although the work was created in the latter part of the 20th century, it still looks timeless. I think the next generation of artists, designers and photographers respond to the work because it draws on modern social themes like race, gender and equality that still feel applicable today.

Antonio Lopez: Let Me Hear Your Body Talk is on view at Daniel Cooney Fine Art, 508-526 West 26th St, #9C, New York; 212-255-8158; danielcooneyfineart.com.

Comments

Comments